Written By: James Marker and Eric Daigle, Esq.

Across the Country, in response to use of force incidents, there is a knee jerk reaction of different organizations to adapt the United Kingdom’s National Decision Making Model into American law enforcement. This article will discuss why this decision is unacceptable, and why it does not represent current case law and constitutional standards. Law enforcement has worked for almost two decades to remove the stair-stepping methodology of the use-of-force continuum, due to its failure to represent the methodology of current case law accurately. We all like new and shiny ways to address problems, but we’ve been down this road, and it’s a dead end. That is, what has worked abroad does not work here.

Over the years, Presidents have assembled commissions and task forces to address “needed change” in response to social unrest; and to find ways to re-connect officers and communities.[1] Improving police policies and training is typically in the mix of suggestions. History repeats itself. Once again police reform is all the buzz, and much of the focus is on reform in police training concerning use-of-force. The President initiated the latest task force, Task Force on 21st Century Policing, to “strengthen community policing and trust among law enforcement officers and the communities they serve.”[2] Leading police organizations are holding conferences, symposiums, and meetings to address the current issues. Researchers and academics are weighing in to find a new way to do a century old job. Why are we changing what has proven successful?

The IACP and Department of Justice (DOJ) Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) held a use-of-force symposium to achieve consensus surrounding the current core use-of-force issues. One conclusion the participants reached was “police professionals were falling short in their duty to train officers.”[3] Symposium participants shared concern that in-service trainings have not been validated in the same rigorous fashion as academy training…,”[4] and “questioned if training had become ineffective because it was based on what an officer could not do, rather than a positive format focused on what an officer could do or, in fact, must do with respect to the use-of-force.”[5] Chief Phillip Broadfoot stated it best, “There is a large body of case law that permits the police to use force that is reasonably necessary to overcome the force used against them. The public often perceives that force as excessive when it is not.”[6] The question then becomes, what do we reform?

In August 2015, the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) completed another national research project report titled “Re-Engineering Training on Police Use-of-Force” containing a summary of the critical issues in policing series. As the author points out, “some of what you will read in this report may be difficult to accept…”[7] PERF invited policing professionals from England and Scotland to participate. “UK police place a high priority on learning how to resolve incidents without using firearms, because the large majority of constables there are not equipped with firearms…so we’ve always had to train differently.”[8] Training differently in the UK means the training is based on the National Decision Making Model (NDM), which is a system that helps officers to respond effectively to all sorts of situations and problems.”[9].”Previously, we hadn’t been giving officers any structure in terms of dealing with use of force. This gives them a sequential model they can use, that helps them create distance and time and avoid using force if it’s not necessary.”[10]

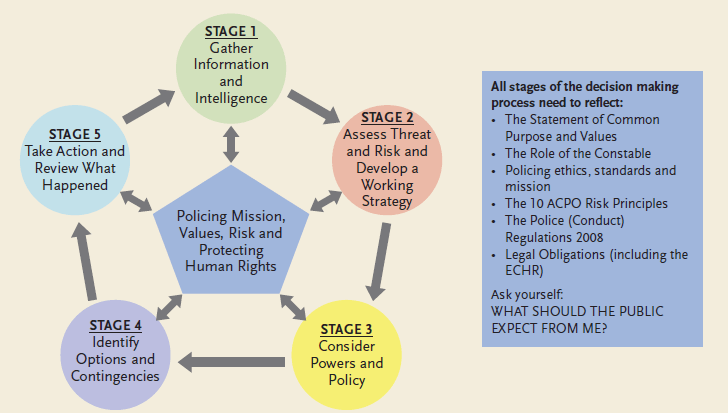

Similar in design and function to the outdated use-of-force continuums, The NDM is a circular sequential decision making process.

The officers asked themselves a series of questions through five stages while en route and on-scene to any call. Stage 1, Gather information and intelligence. Stage 2, Assess the threat and develop a strategy. Stage 3, Consider powers and policy. Stage 4, Identify options and contingencies. Stage 5, Take action and review what happened.[11] If the incident is not over, go through (“spin”) the model again. If the incident is over, review your decision(s) using the same model. In addition, officers’ decisions need to be in accordance with the court’s reasonableness test, which is derived from the European 1998 Convention of Human Rights.[12] The Untied States system embraces Civil Rights.

The European reasonableness test includes four factors: 1) “Proportionate,” meaning “How would a reasonable member of the public view the action that we [officers] took?” Would they think that it was a reasonable response?;[13] 2) “Lawful,” are the actions supported by common law or statute?;” 3) “Accountable,” have they [officers] accounted for other available options?; and 4) “Necessary,” was the use-of-force necessary in the first place, or could the officers have done something else?[14]

In July 2014, Fairfax County, Virginia contracted with the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) to conduct a policy and practice review of the Fairfax County Police Department (FCPD).[15] PERF recommended that the FCPD take a bold step and adopt the NDM. “PERF believes that this type of decision-making model has great potential for police agencies in the United States. “[16] PERF also “recommends that U.S. agencies study the UK model and begin to look at adapting the NDM to their own circumstances and their own policies,”[17] yet recommended “adjusting FCPD policy language to comport with the “objective reasonableness” standard articulated in Graham v. Connor…” as a fundamentally important recommendation in their report.”[18]

Law Enforcement Executives across the country recognize that change in use-of-force response is necessary, but to abandon almost two decades of work is not the proper answer. The continuum was removed from policies and operations due to the fact that it did not properly demonstrate the constitutional standards or “objectively reasonable” decision-making. Departments across the country took a bold step and abandoned the use-of-force continuum methodology and developed a holistic amendment-based use-of-force training program for peace officers, detention officers, and corrections.[19] Still being used today, the Wyoming training model teaches use-of-force decision-making as the United States Supreme Court requested in Canton v. Harris, [Footnote 10]. The need to train officers in the constitutional limitations on the use of deadly force, see Tennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S. 1 (1985), can be said to be “so obvious,” that failure to do so could properly be characterized as “deliberate indifference” to constitutional rights.[20]

The focus should be on how policing is different in the United States versus European police departments. United States police officers operate in an armed society different from our European neighbors. We must keep in mind that a small percentage of officers in the UK carry guns and Tasers. So let’s cut right to the chase. We don’t need a new model to cause confusion, we need to train our officers on clearly established law pertaining to the use of force that the Courts provide to our officers. They need to understand in continuous situational force decision-making training, that poor police tactics that place them in a situation where deadly force is necessary will lead to liability issues. Focus on training officers go avoid poor tactics and hold officers accountable when they violate policy and training.

- 1967 President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice. 1973 National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals. ↑

- The President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (2015). Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. ↑

- “Emerging Use of Force Issues: Balancing Public and Officer Safety Report.” IACP/Office of COPS. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- “Re-Engineering Training on Police Use of Force Report.”: Police Executive Research Forum. August 2015. ↑

- Id. at 7. ↑

- Id. at 7. ↑

- Id at 41. ↑

- Id. at 44. ↑

- Id. at 46. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 47. ↑

- Use of Force Policy and Practice Review of the Fairfax County Police Department (2014), Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) ↑

- Id. at 15. ↑

- Id. at 23. ↑

- Id. at 18. ↑

- Teaching 4th Amendment-Based Use-of-Force: AELE Monthly Law Journal, 2012 (7) AELE Mo. L. J. 501. ↑

- Canton v. Harris, 489 U.S. 378 (1989). ↑