It is clear that 2015 was a very difficult and tumultuous year for law enforcement. Law Enforcement has been the subject of much national critical media analysis, specifically officer use of force and deadly force incidents. As a result, officers and their Chiefs are fearful of becoming the next targets of viral videos, and having their decisions and actions judged by armchair quarterbacks. In response to the scrutiny, the question repeatedly asked is “how do we make things better?” Police chiefs, media, and politicians often respond: “police officers need more training.” Is the solution really more training? If so, in what subjects or areas do we need more training? In fact, I have been surprised with the proposed training topics that have resulted from the recent scrutiny. The topics include: mental illness training, recording police training, and scenario-based use of force decision-making and de-escalation training. All of these subjects share the same common thread; they require the ability to communicate with a subject who is not responding to the lawful authority of the officer.

Admittedly, some police agencies in the U.S. are deficient in their use of force training. Let’s face it, however, we have moved past the training stage. Agencies are merely using the need for training as an excuse, a way to kick the can down the road, so to speak, rather than impose sanctions (discipline) when officers inappropriately use force. One thing is certain, if an officer in your department uses deadly force, the department’s policies and training will be scrutinized, as well as the tactics the officer used prior to the use of deadly force and whether your supervisors hold your officer accountable to department policies and training.

A review of police operations makes it clear that your agencies have been doing more with less since approximately2010. Is the current situation, however, a result of budget cuts, a decrease in personnel numbers, and/or added responsibility? There are a few common responses to training challenges. First, in most police departments, officers find themselves increasingly responding to non-criminal incidents (e.g. incidents involving mental health issues), which uses significant department resources, presents unique challenges, and tests the abilities of your officers. Can the limits of police training really provide an officer with all the necessary skills and options to effectively handle a subject who is suffering from mental illness?

There are two fundamental questions to ask every time officers use serious force: (1) did the use of force violate criminal law; and (2) was the use of force consistent with policy and training requirements, including whether the tactics leading up to and during the force were appropriate. This is the point where departments should determine whether the individual officer needs specific training, or perhaps the department as a whole; or, on a broader scale, whether the department needs to revise the policy and/or training. It is also the point where departments should consider other interventions, including whether discipline is warranted.

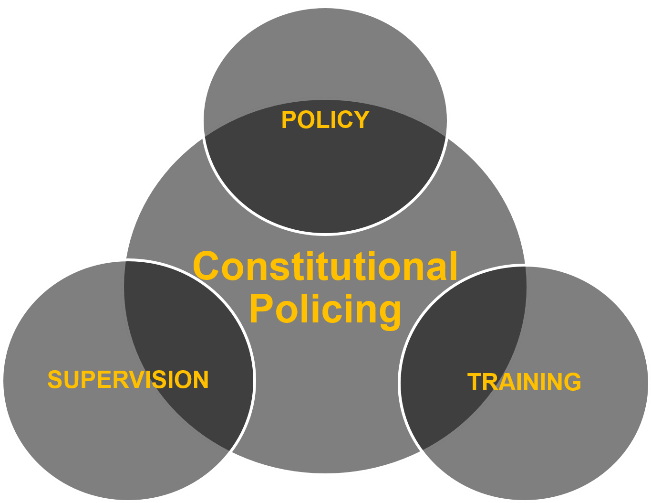

Agencies should also question how they will ensure compliance with constitutional policing, accountability, and community trust. There are essentially three fundamental phases/components to the delivery of constitutional policing: 1) The development of sound, clear, and concise policies; 2) Policy training and, in the case of force, regular refresher training that can be effectively incorporated into annual firearms training; 3) Consistent and constant supervision, including the use of corrective measures when officers violate policy. Ensuring constitutional policing in an agency requires all three pillars of accountability. The methodology of accountability is focused on ensuring linkage between the three pillars. If one of the pillars is broken, the department’s commitment to constitutional policing is failing.

The final principle is “community trust.” It is necessary to work with the community to demonstrate that the pillars are in place, and the department has put in operation a methodology of accountability. The involvement of community members and groups will enhance the strength of the police department. The success of the transparency depends on the quality of the partnerships formed, and the voices that are heard.

Department and organization scrutiny will include a determination of whether a custom/pattern and practice led to a deprivation of constitutional rights. This will be measured by first determining whether the Department: 1) developed policies that are consistent with constitutional/ legal requirements and generally accepted police practices, 2) provides thorough training on all affected policy requirements, and 3) implements and reinforces policy requirements through effective supervision of officers. Carefully coordinated linkages of these three areas will provide the path leading to effective and constitutional policing.

These pillars, as demonstrated by the image below, illustrate the concept that to ensure constitutional policing, a department must have sound policies and procedures; must train officers on the department policies and core tasks; and properly train supervisors on the concept of “close and effective supervision” to ensure the officers are following policy and training.

Policy Development

A police department’s policies and procedures provide the agency with core liability protection. Comprehensive and current policies are the backbone of effective and constitutional policing. A Police Department’s policies and procedures shall reflect and express the Department’s core values and priorities, while providing clear direction to ensure that officers lawfully, effectively, and ethically carry out their law enforcement responsibilities.

Training

It is not enough, however, to simply have sound policies. Departments must train officers on the policies. The United States Supreme Court held in the landmark case City of Canton v. Harris[1] that municipalities have an affirmative duty to train employees in core tasks. The Court stated inadequate law enforcement training may form the basis for a civil rights claim where the failure to train amounts to deliberate indifference to the rights of persons with whom the police come in contact. Deliberate indifference occurs when the need for more or different training is so obvious, and the inadequacy so likely to result in the violation of constitutional rights, that the policymakers can reasonably be said to have been deliberately indifferent to that need. We know that a policy is only as effective as the training on the substance and requirements of that policy. If the training is weak, unfocused or nonexistent, then officers will not follow the policy. It is necessary for agencies to consider how they will distribute the policies; and they must ensure that document management allows for version tracking and confirmation of delivery by electronic or written receipt.

Supervision

Finally, supervisors must hold officers accountable at all times. When the policies are violated, a sound disciplinary process must be engaged. Departments should assess the validity of supervisory oversight practices that promote the identification of employees who are underperforming. Departments shall ensure that supervisors have the knowledge, skills, and ability to provide close and effective supervision to each officer under the supervisor’s direct command; provide officers with the direction and guidance necessary to improve and develop as police officers; and to identify, correct, and prevent officer misconduct.

Supervision is a core principle of constitutional policing and, as such, must be evaluated throughout all areas of the department’s assessment. Supervisory assessment must occur during the review of incident reports, use of force reports, internal affairs complaints, vehicular pursuits, arrests, seizures, and performance evaluations. Departments should implement and maintain an early identification system (“EIS”) to support effective supervision and management of officers and employees, including the identification of, and response to, potentially problematic behaviors as soon as possible. Departments should regularly use EIS data to promote ethical and professional police practices; to manage risk and liability; and to evaluate the performance of employees.

Law Enforcement is under strict scrutiny, but there also appears to be a lot of side-stepping in policing these days. When asked how we will take responsibility for actions, the answer is always “more/better training,” which appears to be a way to buy time and wait out the storm. This simply will not suffice. It is not going to get easier. It is time to put an end to the constant training excuses. It is time for some corrective intervention, not only through effective policies and training on the policies, but also requiring supervisors to hold officers accountable for following policies and training. Instituting the protections of the constitutional policing pillars discussed above will ensure effective accountability. This, in turn, will help to ensure that neither your officers nor your department are the tag line on the next viral video.

389 U.S. 378 (1989) ↑